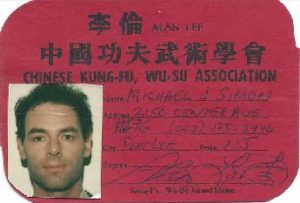

When I was 34 in 1987, I joined the Alan Lee Kung Fu Temple on West 27th Street for two years. I remember the year because many of the other students were 17, exactly half my age, and going to the toughest high schools in New York. Training consisted of one hour of exercise and one hour of lessons and fighting, or as we called it, playing. I was in good shape in those years. I stopped smoking and practiced my horse-riding stance while watching movies on TV. We conditioned our hands by pounding on bags of grain or beans, on concrete blocks and by breaking boards and bricks, which isn’t as difficult as it sounds.

The calisthenics were brutal. The seniors would walk around counting us off as we did pushups and saying things like, “You can cry. We don’t mind.” We were on the 8th floor of a 12-story building so as part of training, we would run to the basement, turn around and run to the top, and then go back down to our floor. The standard way to do the stairs was to take a bit of water into the mouth at the fountain, do the stairs, and then spit out the water. One of the seniors named Keith used to put on about 20 pounds of weights and do the stairs. This effort gave him amazing thigh muscles. The man could levitate with blinding speed to standing from sitting cross-legged on the floor.

My drill instructor had the unlikely name of Candy. Candy’s real name was Candelaria. A stocky woman, she didn’t quite clear 5’ tall. When Candy got down in horse stance, she pretty much disappeared into the floor. Starting from her low position, she was always grabbing for my nuts, a trick that was difficult to evade. She told a story of how she had rolled down an icy flight of stairs in the subway and just stood up at the bottom and walked away. I remember the first time this happened to me—not down a flight of stairs but just walking on ice. I slipped and felt myself going down so I tucked my neck in, rolled, and stood up, a feat which made me chortle, “I got it! I got it!”

My 17-year-old classmates were quick as lightning so I had to learn to think fast to avoid their blows. I would feint, bob and weave, and suddenly strike. I did get hit sometimes but that can’t be helped, so I just kept dancing and did my breathing.

Because I was second-largest in the class, I was almost always paired with a 6’2” ex-Marine named William. His forearms were like steel from toughening on a log of wood we had hanging from the ceiling, and practicing blocking with him was torture. I used to sit this 220-lb. guy on my shoulders and do 100 toe stands.

Sifu Alan Lee was about 70 years old at the time. In the elevator lobby, there were photos of him as a youngster flying and delivering kicks and blows with his sword and staff. He had soft hands but could break stacks of 8 bricks with one blow. He taught the seniors on Sunday and they taught us the rest of the week. We weren’t allowed to watch Sunday practice.

Although we didn’t socialize together much, some of us would go see kung fu movies at the Rosemary Theater in Chinatown next to the Manhattan Bridge. It’s now a Buddhist temple but at the time, it was a popular venue for the films of Sir Run Run Shaw, one of the most prolific kung fu movie studios. Most of us sat in the balcony, which was the smoking section and a popular make-out spot for Chinese kids, who also used to throw grapes on the audience in the orchestra below. When an actor executed a tricky maneuver, you could hear our guys mutter, “Dag!” and other such epithets.

We studied Chinese medicine. As Sifu put it, “To hurt people is easy. You should learn how to heal people. That’s a bit harder.” Sifu mixed and sold his own bruise medicine, an herbal brown liquid that supposedly healed bruises faster. I wouldn’t know about any medical virtues but it made me feel better, at least from the placebo effect. We studied acupuncture meridians and massage. We learned tai ch’i, which has very nice poses to maintain health as I get older.

Over the years, I’ve studied in various martial arts schools and they mostly share the same fault. They don’t break down the moves enough—they just whirl through a movement and say, “Do that.” This never works. Strength depends a lot on form and you can’t learn good form without slow practice before fast practice. With Sifu Lee, we would learn every move slowly first, then tensing like isometrics, and finally at full speed. When you learn a technique this way, you never forget it. It is added to muscle memory and after a while, the motion is automatic.

After six months of training, I could break stacks of bricks or stop an opponent’s breathing. After a year, I was registered with the New York Police Department as a lethal weapon.

I lost all my fear. This was great for my chess and Go skills but a bit dangerous in real life. I had a memorable belly to belly shouting match with a rather large Italian contractor in New Jersey who I judged was so fuckin’ dumb that he couldn’t be connected to the Mafia. They have higher standards than a guy like him. We shouted for a while, both saw we were getting nowhere, and broke up laughing. I made the deal.

One day I was on a very typical New York block—Fifth Avenue between 22nd and 23rd Streets—but nevertheless the foot traffic included some serious fruitcakes. I was coming from a business appointment wearing a suit and I saw the guy of a scrawny, drugged out couple hit the woman he was with. Twice. Acting on instinct, I walked up to him and quoted Bogart in To Have and Have Not, “Go ahead, hit me.” He slunk away muttering while passersby applauded. Characteristically, his woman followed him, probably for more abuse. I shrugged and walked on, and only then got the shakes. What had I done? Supposing he had been armed?

I had been studying at the temple for two years when a few seniors called me into the office. “We’d like you to run the office, Michael,” Luis told me.

“I’m sorry, I can’t do that. I already run a chess club, I have a job, and my wife is sadly neglected.”

“Uh, we’re not exactly asking. Community service is required of our members.”

“Hmm, let me ask you a question. Suppose I wanted to change the way you run the office? Could I do that or do you just want me to follow the way it’s done now?”

“You’d have to follow our instructions.”

I shook my head. “From what I’ve seen of your office, I don’t think I’d enjoy that. Sorry.”

“Well, it’s a requirement to your study here.”

“Then I guess I have to quit,” I said sadly. “I really can’t do this. Thank you for teaching me this much, and thank Sifu for me, too.”

I changed back to my street clothes and left. That they let me leave without negotiating proved to me that they were bad at business. That I left meant that I wasn’t all that dedicated to learning to fight. I had achieved my goal, which was to become strong. I didn’t need to devote my life to it.

My best alternative from there was a group that studied capoeira, the Brazilian martial art. After calisthenics and basics, we would all line up in a circle, clapping or playing instruments in a samba beat. The leader would appoint two players to start. They would get in the middle of the circle and play. The moves included normal punches and kicks but also cartwheels and floor work, using the legs to try to trip the opponent. After a minute, the leader would call for the next two players. It was loads of fun.

I had some difficulty because capoeira moves are reversed from kung fu. For example, the basic stance in a ginga dance pose extends the left hand when the right foot is forward; in kung fu, it’s the reverse. I was constantly getting confused. I tried hard—when the ginga is done right, the fight ends before it starts because it looks so scary.

Of course, my punches and kicks were strong from kung fu and I could do a passable cartwheel but the floor work was hell. One move was to throw yourself face first onto a sort of pushup position while looking backwards over your shoulder, and then kick or move backwards toward the opponent. The art seemed designed for lightweights, skinny people who didn’t need to exert so much force to keep from falling flat.

A master from Brazil came up and we played briefly. I couldn’t hit him with a flurry of punches so I cartwheeled out of his counterattack. I came back to ginga facing him and he went down for a trip move but he saw I was ready to stomp his leg and changed his mind. Fortunately, the round ended before he properly kicked my butt.

The teacher wasn’t very systematic or articulate in English so it was very difficult to make progress. I quit martial arts, even though I still do moves when alone in the elevator and run through some tai ch’i when I’m in the mood.

Many years later in Japan, I heard of a rather violent foreigner who got beat in a business deal and broke the other guy’s leg brutally. He was an automobile designer and I could imagine that his opponent was a typical arty type, unprepared for physical violence. I happened to be introduced to the guy in a Nishi-azabu bar and he seemed right enough. I wondered about the story.

We talked about fighting and it turned out he had been a Navy boxing champion and then put himself through design school by boxing for money. “Do you keep it up?” I asked him.

“Keep what up?”

“Do you stay in shape?”

“Why, wanna see?”

We went out to the alley. He put up his fists and without taking my eyes off him, I did a kung fu salute, a slight bow while wrapping one fist in the other hand. I relaxed and started dancing with a faint smile, unafraid. He came in pretty fast with a couple of punches that I blocked and then I was startled by a side kick that mysteriously stayed up. In kung fu, we retract our limbs quickly. I grabbed his leg with my left hand and feinted two quick groin kicks to let him know he was in trouble if they had connected. I then pushed him back to the wall while fending off his punches with my right. He hit the wall and I backed away.

I saluted again. “Thank you,” I said, trying to end it nicely. “You’re much stronger than I am.”

“You blocked two of my serious punches, dude. That’s pretty good, yourself.”

We didn’t become friends. I haven’t played since.