I had a Jewish deli in Tokyo. Really. It was a sandwich shop that we set up across the boulevard from Goldman Sachs, Morgan Stanley and the still extant Lehman Brothers of 1998. We served matzo balls and Reuben sandwiches to the bankers and to the U.S. embassy employees who lived up the street in a sort of dormitory.

The research I did for this project was intense and challenging. I made a dictionary of American and Japanese food words like “to boil” and “to simmer”. We developed recipes and I taught a local baker how to make challah and Jewish rye, and a local meat smoker how to make corned beef and pastrami. We got the wholesale prices of ingredients and calculated the cost of our products to the gram so we could figure what we needed to charge for them.

Do you know what’s in a real Russian dressing? It’s a mayonnaise but not made with ketchup. It has beets to make it red, horseradish to make it tangy, and a few lumps of cheap caviar to make it Russian. We put this elixir on our Reuben sandwiches and the customers went wild for it.

The project started when my girlfriend Kanako met a friend of hers for a coffee in Minami-Aoyama and the lady mentioned that her new boyfriend was Jewish. “That’s funny,” Kanako replied, “so is mine.” The ladies decided to introduce us and a few nights later, we all went to dinner in trendy Daikanyama at the formidable institution called Tableaux. The anchor restaurant of the public company Global Dining Inc., it had been started about fifteen years previous and had exploded into a restaurant empire based on affordable Continental food in a Japan where this was all news.

The other boyfriend turned out to be an Israeli ex-paratrooper named Hanan. He was very fit and I could tell that he knew how to show a girl a good time, which accounted for his popularity in Tokyo. I asked the New York question, “What do you do?” and he said he worked security for the Jewish temple. I didn’t know there was one but indeed, it had about 2,000 members, most of whom barely managed to show up for the major holidays.

“And vaht do you do?” he asked me in turn.

“I do venture capital,” I lied to pique his interest. “Tell me a deal.”

“You know vaht I alvays vahnted to do? I vahnt to open a Jewish deli in Tokyo.”

A stunned silence ensued while I digested this. What he couldn’t know was that my father and his brothers had opened European style delis across New Jersey in the 1930s, starting the businesses up, flipping them, and then moving to the next town. “What did you say?”

“I vahnt to open a Jewish deli in Tokyo.”

Here was a business that wouldn’t take much capital, would teach me a lot about Japan, and that resonated with my life and origins. “That’s a fantastic idea. Let’s do it!”

“I know a guy who vill help us. He runs a vine company here. Let’s meet him.”

The fellow in question turned out to be the epitome of the old Tokyo hand, Ernie Singer. Hanan and I went to his office in Kanda, a commercial hub a few kilometers north of Tokyo Station. His company was called Millésimes and we entered an office of about 40 people, all selling wine like crazy. We were shown to the executive suite and Ernie stood and moved to a large chair, motioning for us to sit on the couch opposite. A bulky fellow of 55 or so dressed in business casual but with a pocket square, Ernie grinned affably and offered an ashtray. I pulled out my Havana panatelas and lit one.

“Sorry I’m going to stink out your office,” I said.

“It’s no problem,” Ernie replied. “I understand you want to start a Jewish deli?”

“Let’s say I’m investigating the possibility.”

“You know there was one in Roppongi until a couple of years ago?”

“I didn’t know,” I replied. “Tell me more.”

Here began one of the tales that I came to prize Ernie for, one mixed with equal parts lies, exaggeration, and ah, business opportunities.

“About ten years ago, I met a nice Jewish woman from Las Vegas named Anne Dinken. Her husband had discovered some get-rich quick deal here in Tokyo and went off to make his fortune. She heard from him only intermittently for a year or two and finally got on a plane and came here. Sure enough, she found him shacked up with a Japanese girl. She filed for divorce but in Japan, it takes about two years of lawyering to get one. While she waited, she opened a Jewish deli in Roppongi. To her surprise, after a year she started doing about $2 million of business. She got the divorce and everything looked good. But then she got cancer. She sold the business, went around the world, and then died at home in the U.S.”

“Wow, what a story!”

“Unbelievable, isn’t it,” Ernie smiled.

My eye clocked a Go set on a table in the corner. “Do you play Go?” I asked him.

“I do,” Ernie answered.

“How strong?”

“I’m about shodan.” Go is an Asian chess-like game of strategy in which players are ranked in dans like karate belts. Its excellent handicapping system means that players of disparate strengths can still enjoy a game. Shodan or one-dan is a good player.

“Great, let’s play sometime. I’m five or six-dan,” I told him. “I was director of the New York Go Club for a few years.”

“Sure. You can come here for lunch and then we’ll have a game.”

The conversation turned back to the deli. “What kind of corporation should I have to run the deli out of?” I asked.

Ernie told me that a K.K. like a public company wasn’t necessary—the costs of formation and operation were too large. The Y.G. form of limited company would be fine, what in the U.S. would be called an L.L.C.

“I guess it can’t be helped, I’ll have to make a Y.G.,” I concluded.

“I happen to have on old Y.G. I could sell you,” Ernie offered.

“Really. That would be convenient. But I’d want to name it,” I objected.

“You can change the name for about $100. That’s no problem.”

“That must be cheaper than forming a new company. Hmm, let’s call it ‘Kosher Y.G.’ Can you have your people do the name change before I acquire it?”

“No, but they’ll do it right after you acquire it. The only thing is, it pays some people’s salaries and that might take a while to wind up. Unless you don’t mind paying them until they find a new entity to get paid through…”

“That’s probably no problem but I’ll ask my accountant. I have a wizard accountant,” I explained. That was true. Morris was a wizard.

Morris Silver trained at Price Waterhouse from his late adolescence until he was a master. After he retired, he kept only a few clients and people they introduced, and focused on billion-dollar estates and the transactions of their principals. We were introduced by one of my members at the Go Club. We quickly became friends and although I wasn’t nearly in his league, he took me on for the amusement value.

I asked him about buying Ernie’s company and he said that if I had an indemnity signed by Ernie for any acts preceding my purchase of it, I could look at it as also buying Ernie’s old hand advice and introductions in my new territory. It was clear to Morris what Ernie was up to. “He wants to shield the salaries from the other company he owns. There is a thing in accounting called transparency and there are two ways to be transparent. One is you can make the item clear to anyone reading your numbers. The other is you can make the item disappear.”

“You’re probably right. The paperwork for the old company came in and you’ll never guess the name: K-Y Corporation.”

Morris chuckled, “The sex lubricant?”

“Maybe. In Japanese, it means kūki yomenai, ‘can’t read the atmosphere’, like a schlemiel who doesn’t look before putting his oar in.”

“Or a mark,” Morris guessed, “Like you, Mikie.”

“Swell.”

“Oh, and let me see what my Las Vegas contacts can turn up for Anne Dinken.”

A few days later, Morris called with news. “Anne Dinken’s maiden name is Tobin. She uses that name now. I talked to her.”

“Really!”

“Her comment was, ‘Ernie Singer? That bastard? What’s he up to?’” We both roared with laughter.

“It seems that a) rumors of her death were exaggerated and b) Ernie knew her a little better than he let on,” I observed.

“Yes. She seemed to think that Ernie is mischievous but not evil. We can do business with him if we’re careful, that sort of thing.”

“Well, we are careful.”

“Humph. Send every piece of paper to me with a translation, please.”

“Yes, sir.”

I went to see Ernie at lunch, gave him a Go lesson, and in exchange he told a story about being in Las Vegas in the ’seventies with a friend of his whose entire aim was to sleep with a prostitute. The shy pal insisted that Ernie keep him company, and moreover, being the wheeler dealer that he is, Ernie found himself charged with setting it up. At the time, he was working for Caesar’s Palace, chiding runaway Japanese who didn’t pay their debts. He said it was easy. Because most gamblers are repeaters, he simply explained to them that they could never play again if they didn’t pay. You’d think they’d be relieved to learn a cheap lesson and just walk away but amazingly, most of them paid.

Anyway, when they arrived at Caesar’s, he was dismayed to find that none of his contacts were in town. He consulted the bellhop, who casually asked him what would be required of the ladies. Ernie said their tastes were simple. After an hour’s wait in their room, they opened the door to find two platinum blondes in bright red miniskirts, foxes in the 120-degree heat, boots, the whole costume. Ernie reported that they were sharp and funny, and knew their trade well. He said they had a nice time and afterwards, the girls wanted him to walk them to their Corvette so the hotel staff wouldn’t bother them. And here’s the funny part. Ernie said that walking the half hour or so through the enormous hotel to the door was more fun than the sex. The looks he got with these two lovely women on his arm, lethal from the wives, lecherous from the men, was totally memorable, whereas the sex was quite forgettable.

In the beginning, our deli used to import Kosher corned beef and pastrami from a wholesaler in Brooklyn. Since Kosher meat is a rarity, I went to Tokyo’s Jewish temple in Nishi-Azabu to try to sell them some. The kitchen staff told me to see the Rabbi, so I waited in the lobby and presently he came down the stairs.

A friendly fellow about 5’9”, with a charming rotund grin and a casual attitude, the Rabbi attempted to frighten me, “You know, kashruth, or the science of being Kosher, is a very strenuous doctrine.”

I tried to ward off any lectures about how to boil the employees and so on, “We use the A to Z Kosher Meat Products Co. from Grand Street in Brooklyn.” I added a frosty tone, “They are responsible to a higher authority.”

“Really? I’m from Brooklyn myself. Who do you deal with there?”

“Eddie Weinberg.”

“No fooling! How is he?”

“He is fine and not exactly getting rich from my business. Anyway, I know something about kashruth. I went to Yeshiva.”

The Rabbi was shocked to learn that my rock ’n’ roll demeanor and hard blue-collar physique had this origin. “You went to Yeshiva? Where?”

“Paterson, New Jersey. Yavneh Academy.”

The Rabbi digested this, “Did you forgive them yet?”

I was amazed that he knew me that well in two minutes. “No,” I laughed. “Rabbi, I would love to defray some of the cost of shipping the product to our deli by selling some of each shipment to you.”

“This we can do, especially around the holidays.”

“Great, I’ll send you a price list and we can discuss the amounts of your order by email.” I handed him a card. “Lovely to meet you.”

I happened to be in Ernie’s office the next day so I told him about the Jewish Center. He said, “I was there the other day for the holiday.”

“Really. I didn’t know you were a member.”

“Sure. I help them with employee issues. I hire their Philippine staff and so on.”

“Ah.”

“We were all lining up to go into the main hall when one of the security people told me that the cops want to tow away my car. I ran down and there’s this nitwit cop who seemed to be the only one on the Tokyo police force who didn’t understand Jewish New Year and was ready to impound my car. I got really mad and you know, when I get angry, I only get colder and more calculating.”

“Oh?”

“It doesn’t do any good to get hot or excited.”

“Naturally,” I said blandly, even though I get hot and excited every time. Self-control has never been one of my strong points.

“I called the guy what I think is the ultimate Japanese insult: ningen no kudzu.”

“A human weed?”

“More like a human turd.”

“And did that go well for you?”

“The cop apologized and left without giving me a summons.”

I was amazed. “Really. I’m pretty sure that I would have gotten a summons for the same behavior.”

I went to Ernie’s office weekly for tea and sympathy. The restaurant business is like the mumps or chicken pox—you get it once, it’s uncomfortable, and then you’re immune. Suppliers like Ernie were waiting to sell you shit, see you go bankrupt, and then buy it all back at half the price. True, this happens less with wine than with say, stainless steel kitchen furniture but that’s only because a failing restauranteur drinks up all his wine.

Our conversation turned to early translations of Japanese literature into English. It turned out that Ernie had read Japanese history at Yale and knew quite a bit about it. But I thought his most interesting topics had a more ah, practical side. I mentioned that I had studied with Donald Keene at Columbia and Ernie was suitably impressed. Keene not only liked kabuki but was also an opera buff. He claimed that he had been to see Don Giovanni seventeen times and each time had been more boring than the last but that this was the sort of thing one did as an opera buff. According to Keene, there were ushers at the kabuki and they might report to the emperor, who was putting on the show from his royal coffers, that you had left early. This problem was magnified by the very length of kabuki shows, sometimes running over eight hours. Even the fantastic bento box lunch couldn’t hold your attention for more than an hour, and then there were the other seven. A few sips and a nap and you still had four hours to go. He said that the kabuki was one of the few types of theater with an exit fee as well as an entry fee. You had to pay the usher if you wanted to leave unnoticed.

Keene was one of the most prolific translators in the fifties. Japan had lost the war and was a wasteland waiting to be explored. Ernie told me that most of that early generation of Japanese translators had come to Japan to scoop up little girls and boys, who not only were cheap at the time, but also many were trained in the coquettish arts of the wakashu—young playthings.

“It makes sense,” I said. I had heard about Keene pouting in his Tokyo Station office because the literary intelligentsia of the 1950s and ’60s like Yukio Mishima wouldn’t look at him. He got no respect, even if he spoke Japanese better than most of his stable of writers. As I well knew from even my short stay in Japan, the isolation he faced must have been terrible.

My own tribulations in Japan weren’t nearly as bad but they weren’t fun. One evening I called a manga artist named Robot, who I thought was my friend. I said, “I’m feeling a little lonely tonight. I want to bring a bottle of beer and two glasses to your place, stay a half-hour, and leave with the glasses. How about it?”

“Ah, how about next Thursday?” Robot asked.

“Let me get back to you.” I hung up on him and never talked to him again. I don’t know what’s standard in Japan but this is not how a friend behaves in my country. Read Martin Buber’s I and Thou twice and call me in the morning, fuckhead.

A year flew by before I knew it. Adding up the numbers on the anniversary of the setup, I realized that I was at the end of the amount I had allocated for this project and it was time to wrap it up before it did even more damage. I called Hanan and had him announce to the troops that there would be a staff meeting the next morning.

A group of fresh faces surrounded me as I explained my position, “We’ve been losing about $4,000 a month. When I started this deal, I set an upper limit on how much money I would invest and lose before closing or selling out. You guys may have jobs tomorrow but you’ll have to show me how we can make any money. I can’t see it from these numbers, that’s for sure. And you can’t say that I haven’t been patient—a whole year!”

Nobody had any suggestions so I said, “Well, it looks like we’re closing. In my perfect world, you guys would work for another two weeks or one month and terminate peacefully. However, that’s up to you. I’d like to know what you want to do.” I turned the floor back to Hanan.

He pushed them to quit immediately and they did. They all left without further ado, without even recording a new message on the answering machine, without caring a bit about the customers. Hanan then quit Ernie’s company owing him a few thou for wine samples that he must have sold. Morris told me, “Michael, you and I are equally good friends to our friends. But I’m a much worse enemy to my enemies.”

We had another year on the lease so we decided to pivot to a gourmet deli rather than a kosher one. We kept the corned beef, pastrami, and Reuben and added some salads like a Cobb and a Niçoise. We came up with a roast chicken, Brie and mango sandwich with lemon aioli on a sourdough roll.

Kanako insisted that we use a bookkeeping system that everyone could understand, based on paper forms. We had serious fights about the store and I wondered if the silly place was worth all the craziness.

We interviewed a few chefs and had one or two cook dinners for us. One fellow confused two unlabeled jars of salt and sugar. The lamb chops were ruined and the peach pie was too salty to eat. We threw it all out and ordered in pizza. The next day, the fellow called and asked if he could try again. “No,” I told him. “You’re probably just unlucky but I can’t bet my restaurant on your luck. Sorry.”

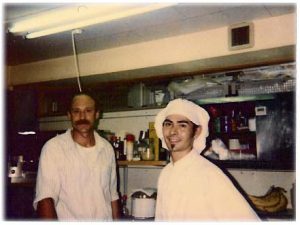

The next chef we interviewed was named. Stephen. Of slight build and medium height, black hair cut rather like a Mohawk but with no perceptible lift on top, a Satanic would-be goatee, and piercings here and tattoos there, he looked more like a guitar player than a chef but soon quickly proved that he could move quickly and accurately in the kitchen for ten hours at a stretch. He got the job.

Stephen quickly realized that we couldn’t pay to import smoked Scottish salmon. “What about gravlax?” he asked and I realized it was a very good idea. We toyed with recipes for a few days and then it became a regular menu entry. It was a little weird on a bagel but the bagels weren’t so great to start with. We couldn’t get high enough gluten flour.

We were looking for a part sous-chef and part dishwasher so I came up with a test that could show us what the interviewees could manage: cut an onion. It was practical and kind of Zen at the same time. We took the cheapest of vegetables, the one with which everyone begins any recipe, and made a phenomenological study of its humble origins.

One joker held the onion between two fingers and cut in the middle of them. “Stop!” I shouted. “I don’t have insurance. Good-bye!” In fact, Japan’s tort law protection is weak so the fellow couldn’t have sued me but I didn’t know that at the time.

Another guy asked, “What’s the onion for?” and I told him it was the first time anyone had asked this and added, “Medium dice for a fish entree,” and he did what I thought was a passable and quick dice. Stephen threw out the onion with disgust, an act that not only ignored the rules of our test scenario but also wasted food and its cost. The applicant left. “That guy makes ugly food,” he declared and said that he would gladly pay for the onion. I figured it was a chef thing.

One day, an English-speaker called and demanded to speak with the owner. Kanako took a message and I called the fellow back from the car. He worked at Goldman Sachs. “Charge me what you want,” the fellow said, “but put a lotta meat on my fuckin’ sandwich, OK?”

“Can do, sir,” I replied. “Next time ask for the Sumo Size.”

We operated for another year and I sold the place to a Japanese company. Sadly, they didn’t last. Their staff didn’t speak English and many of the customers couldn’t speak Japanese.

A year later I got a call from Hanan. We went to a noodle shop near Shibuya station and ordered beers. I told him it was a pleasure to see him. He was doing OK in his former job of security for the temple and he was cooking there part time as well.

“That’s great,” I said, “you shouldn’t let your talent go to waste. You’re a good cook. I’m not nearly as good.”

“No, you’re not,” Hanan replied. I smiled sourly at this. He asked me if I didn’t resent him somehow.

“Hanan, I always liked you. My firing you had nothing to do with you personally. You just didn’t make money, that’s all. I’m not a charity. I couldn’t afford to lose any more money. What’s mysterious about this?”

An old friend in the restaurant business emailed me about a funny article in the New Yorker written by a New York restauranteur who had a steak joint in Tokyo. On my next trip to the Apple, I called his restaurant and asked to speak to Tony. When he got on the phone, I said simply, “Hi, I had a Jewish deli in Tokyo.”

“Really! Are you in New York? Can you drop by?”

I went to Les Halles around 4:30 and sat at the bar with Tony Bourdain, the food writer and TV personality. A few years younger than I but with a full head of graying hair, we talked about drugs, restaurants, and drugs. I told him that I was a rank amateur when I started the New York Deli and was still very far from professional at the restaurant business. We discovered we had attended the same posh high school in New Jersey, which was an amazing coincidence. I asked him how he could possibly afford the steaks they had served in Tokyo, 3” thick monsters which, if bought in Japan, would have cost more than he could sell them for. He told me they shipped them from New York.

I was flabbergasted. “We used to send kosher meats from Brooklyn and fish from Russ & Daughters but it was far too expensive.”

“Right. That’s why we closed. Tokyo is a really tough market for food.”

“There are 160,000 places to eat and drink in Tokyo. The competition is fearsome,” I said. “The bathroom installation costs more than an entire restaurant in Manhattan.”

Tony had only been in Tokyo for a couple of weeks. He recognized that Japanese employees were excellent, complete with photographic memory, tireless diligence, and a work ethic second to none.

Kitchen Confidential wasn’t out yet and he said that a TV station wanted him to do a show. “My life is about to change big time.”

“It sounds great. I’ll be a loyal fan, I promise.” Kanako came in and we sat down to huge steaks. We had fun.