They fill you with the faults they had

And add some extra, just for you.

“This Be the Verse”, Philip Larkin, 1971

For a century, my family has been preserving a bunch of factoids about their history, stories told to bolster our psychological positions in relation to acts that have long since been long forgotten by anyone else. Feel free, dear relatives, to tell me if you detect any falsehoods. Despite my best efforts, I’ve long since lost the ability to tell.

My father Dave was born in 1904, youngest of seven children of Russian Jewish immigrants, and the first to be born in their new country. Dave’s father was a modest landlord, who owned some walk-up tenements in Paterson near the Great Falls. The tenants were so poor that he had to give them money for coal in the winter or else the pipes would freeze. He also was the gabbai of his temple, an assistant to the rabbi. Dave’s mother was blind from diabetes.

His two sisters married off. His oldest brother Bernie fled and made a good living in the manufacture of Arrow Shirts. The other four brothers joined forces and went into the food business. During the 1920s, they would move to a town in New Jersey that didn’t yet have a European deli, open one, and flip the business to a local. They did this in Butler, Dover, and several other towns.

After that, they settled in Hackensack. They had the butter-and-eggs stand in a supermarket, which at the time was not one big store but a collection of vendor stalls much like Les Halles or provincial markets all over the world.

Being the youngest, my father was tasked with the job of taking the ferry to New York to buy butter and eggs. He would go to Harrison Street, near the Mercantile Exchange. The SPCA had put a trough outside the Exchange to provide water to the horses that customers had ridden at breakneck speed to make a deal, and which would otherwise expire of thirst in the hot summer sun. A madman, his mind ruined when he lost his capital, stood next to the trough, drinking from it occasionally and waving customers away, “Go back! The game is rigged! You’re going to lose all your money!”

The year was 1927, two years before the Crash. The madman was right.

Dave favored a butter distributor on Harrison near Greenwich Street. He would drill his T-handle augur into barrels of butter to taste the bottom for rancidity. When satisfied, he would buy an eighth of a railroad carload or about 20,000 pounds for the brothers’ account. If they could profit from selling the contract, they would, but if the futures price went against them, they could take delivery and sell the goods in the supermarket.

When my father interviewed prospective countermen, he checked for flat feet, which to him was a sign of authenticity, as standing and serving all day long tended to produce this symptom. Eggs were 10 cents a dozen but cracked eggs were 5 cents, so periodically a young smartass would ask the partners to crack him a dozen. Or the smartass would call on the telephone, which was still a relatively new invention, and execute a verbal spamming: “Do you have Chase and Sanborn in a can? You do? Well why don’tcha let ’em out?”

Credit Dave and his brother Phil with figuring out that the person really making money in the market was the owner of the building. Accordingly, they started building markets and renting them out in turn. As the supermarket business matured, they copied the pioneer, the Great Atlantic & Pacific Tea Company, better known as the A&P. They got rid of their vendors and owned the whole market. They had the Half-Day Market in the Bronx and the Full-Day Market in Hackensack.

During the Depression, professional boxers couldn’t afford the gas money to get up to the training camp at Greenwood Lake. Dave set up a boxing ring in the basement so they could train at night. During the day, the boxers worked carrying cases of goods. His market was never robbed.

After the war, Dave and Phil sold their food business to A&P and pivoted from markets to warehouses. They built five warehouses in a row in Englewood and sat with them for two years, nearly going under, but fortunately all five sold within a week. Dave walked into his bank with a safety pin on his pocket.

“What’s that?” his banker asked.

“You’re never getting in there again,” Dave replied.

As he aged, Dave told stories of his youth in Paterson, New Jersey’s Jewish ghetto. “A horse died on Wojciekowski Street near Main Street and the cop pulled the horse around the corner to Main so he could spell it in the accident report.” He’d always finished this by laughing at his own delivery.

Dave and Rhoda met at a golf course in 1947. Dave had gone to buy it and was looking around when he came upon a woman at repose in a hammock. He started swinging the hammock in a friendly way, and they got to talking. They spoke English so the broker wouldn’t know that he was Jewish. In the late forties, golf-course owners could have been ostracized for selling to a Jew. The broker followed Dave into the locker room as he was changing back to his regular clothes from his golf outfit, noticed he was circumcised, and refused to sell him the place. It may seem incredible now but Jews were the target of racist attacks in the 1950s. In fact, my name is Michael J. rather than Michael Jacob Simon to conceal my Jewish origins.

Dave tried hard to keep up with the technological changes of the 20th century. His first car was a Nash and his second a Pierce-Arrow, which he called a Fierce-Sparrow. The first time he saw me use an ATM cash machine, he was astonished. I bought him a fax and he used to love watching real estate deals spew into its output tray.

Rhoda was born in Brooklyn a year after her mother got off the boat from Russia. Her older sister Muriel was born in the “old country”. The family learned English with no accent although they spoke Yiddish at home to my grandmother Jenny.

Rhoda’s first marriage was to her sister Muriel’s husband’s brother, a teacher of charm and voice named Max Rich. He was a songwriter most famous for the 1931 tune “Smile, Darn You, Smile!” which became a Merrie Melodies cartoon and the finale of Who Framed Roger Rabbit? During their ten years together, she absorbed the essence of his lessons, learning to be poised and to dress well. The last straw that made her divorce him was that he didn’t come to her mother’s funeral.

My uncle Murray owned a lunch counter in New York’s Garment District. His wife Muriel worked the counter and the register, but it was the Thirties, times were bad, and they didn’t sell much. In fact hungry customers stole so many of the salamis from their windows that Murray had to borrow handcuffs from the police and shackle the salamis in place.

The mafia came in and demanded payola. Aunt Muriel tried to throw them out but Murray came running out of the kitchen and interceded. “Don’t you know who these men are?” Turning back to them, he said that he would feed them whatever they wanted but he had absolutely no money. They declined his mushroom-barley soup and left in disgust.

Murray was our family’s star comedian. Just as my mother’s father spoke eight languages and I speak only four, Murray was twice the comedian than I will ever become. He had been a vaudevillian before that theater was renamed burlesque and they got into short-skirted dancing girls. He used to warm up the crowd in the summer at Catskill resorts before main acts like Jerry Lewis or Sammy Davis Jr., and when people asked what he did in the winter, he would shrug and say, “I put on an overcoat.” The man could double-talk Russian so you would swear he knew the tongue but it was all gobbledygook.

After the lunch counter closed, Muriel worked for an engineering firm as a statistical typist for 30 years and was very organized. She knew Murray’s entire repertoire of jokes and would say, “Tell the one about Zadie,” or “What about Moishe.”

“Two guys meet on Orchard Street one day and one says, ‘Oy, Moishe, that’s terrible, I heard about the fire in your store last Thursday.’

“Moishe is very upset and waves his hands for silence, ‘Shhh! It’s next Thursday!’ ”

One day, Murray and I sat together near the back of the table at a family dinner. Rhoda was describing her little dog Tike, who had his own raincoat and a little house, his own little swimming pool…

“His own tennis court,” Murray mumbled. I totally lost it. I so badly wanted to be funny but I had no idea how to go about it. Dave and Rhoda sure as hell weren’t funny. I got no instruction in the matter.

Muriel told me about the scene when Rhoda told her mother that she was getting married again only six months after her divorce.

“Does he have money?”

“I don’t know,” Rhoda answered.

“Does he have a nice car?” Jenny asked.

“It’s sort of dirty and it has bricks in the back seat.” They were samples for his new warehouse project.

“Can he provide for you?”

“I think so.”

He could and did. Dave and Rhoda had a fancy wedding at the Sherry-Netherland Hotel, Fifth Avenue and 59th Street. They took their first apartment on Riverside Drive near 80th Street in Manhattan, which in 1949 was a very trendy neighborhood. They lived in the first high-rise building that featured a swimming pool on the roof. Dave hated New York, where he was just another yokel, whereas in his home state of New Jersey, he was a dynamic businessman, and this despite his high school education, which seemed to consist mostly of lovely longhand writing that was judged for form and not for content. Plus, he had achieved his objective in coming to the big city. His new wife was attractive and knew how to project status. His one desire was to return to New Jersey and show her off to his friends.

Shortly after I was born in 1953, they moved to Teaneck, a New Jersey suburb of New York with the first signs of civilization jutting out of the farmland. The main street backed onto fields of corn. Jersey land was cheap and trading was so hot that Dave carried purchase contracts in his glove compartment. He sold a piece in Fair Lawn that was developed into homes for veterans at $3,995 with no money down. The George Washington Bridge had just been built and the W.P.A. laid a highway to Paterson called Route 4, where the first shopping mall in the world would be developed in Paramus in 1955.

When it became apparent that their neighbors the Dorfmans, a meek couple in their twenties, were expecting a baby girl, the suburban “keep up with the Joneses” impulse suddenly took specific form. Rhoda, however, couldn’t have children. She had suffered problems that led to her losing a child with her first husband, and the doctor had advised her not to try again. If they were to procreate, it would not be by physiology. Dave called a lawyer.

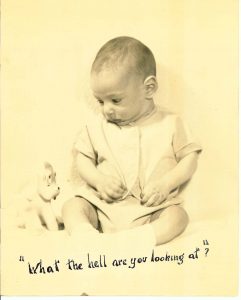

The lawyer knew a Jerseyite whose granddaughter was about to have a baby out of wedlock. That would be my birth-mother, who left her hometown before having me. By February 1953, a white, Jewish baby boy was squalling in Dave and Rhoda’s crib. That would be me.

As a new parent, Rhoda attempted to wash my milk bottles but in the end, she complained so much that Dave called an agency specializing in housekeepers and a white-haired German dowager named Sylvia Landsberg arrived, singing opera and fumbling with the bottles in Rhoda’s stead. Sylvia had lost her entire family in the Holocaust. She lived with us until I was nine and taught me a bit of her language like, “Ach du lieber,” which means something like “Oh my gosh!” She dressed in cheerful prints and played Rosemary Clooney and Frank Sinatra endlessly. She eventually moved to an apartment in Washington Heights and later to a nursing home on the Grand Concourse in the Bronx, coincidentally not far from where my birth-mother grew up.

Dave built a house on top of a hill in Teaneck and became very active in the local temple. His father had been trained as a rabbi but never accepted a congregation. He was on the building committee, he was a trustee, he supervised the construction in progress, and he was duly called to the torah on holidays that all might see he was devoted. Dave felt that at last he was becoming a mensch like his father.

Dave and Rhoda gave me a book called The Chosen Baby, which described adoption as a process in which twenty or thirty babies were lined up and the prospective parents picked their child off the shelf. Rhoda charmingly adopted this myth as her own. I was about eight when Dave asked me if I wanted a brother or a sister. I replied as mildly and carefully as I could, “No, I don’t think so.”

I went to Yeshiva, a sad institution in the city of Paterson, which had been a total disaster area since the T.V.A. brought hydroelectric power to the South and the waterfall towns in New England all died. At least Yeshiva instilled in me Jewish pushiness and devotion to knowledge as ends in themselves. I went as fast as I could manage in mathematics and slow as a cultural illiterate in English. We children were bused to the school from our respective towns so my choice of chums was restricted by the few who happened to live in Teaneck, though these relations were cemented during the hours on the bus to and from school. We played tackle football with no padding or helmets but somehow nobody got hurt.

My parents were just like the New Jersey they wanted to be a part of: cheerful and cheap, energetic but incurious. They had leather-bound English versions of Voltaire in red and Balzac in dark blue, and I read them, cutting the pages with a letter opener as I progressed through Candide and Eugénie Grandet. In our dining room, there was a marble bust of Aristotle that they had bought on a European cruise, and Rhoda used to joke about Aristotle the “philosophe”, pronouncing this with a Yiddish accent. As my education got more intense, she compared me to him.

Summers, I went first to a day camp, then as I got older, to a sleepaway place where I would stay away for two months, the maximum. I still remember the other kids in their bathing suits, the long stupid games of baseball, an episodic and boring sport when beginners play it, my first erections and my first autoerotic experiences late at night under the covers in an open room with ten others sleeping nearby. One arty counselor could recite Gilbert & Sullivan’s Iolanthe from memory for pages while bobbing up and down by bending his knees to the rhythm. I learned a bit of boxing, football and basketball. The food was even worse than at home, and I was almost glad to get back to Yeshiva.

My school day would begin at seven, when Rhoda, an early riser, would call to me from downstairs. Sylvia would have prepared some toast and my glass of milk with a bit of coffee to make me feel grown up. I would get on the bus to Yeshiva, do some jouncing homework in social isolation, and eventually arrive totally bored and rumpled to a fenced compound that was like a prison in the shtetl. The teachers were dour about their prospects in this backwater, and made their frustrations apparent in their treatment of the kids. At five years old, I was drafted to go around my neighborhood selling Israel bonds. The year after I graduated, the Principal was arrested for hitting the children.

Dinners at home were unbearable. Rhoda had some recipes from her mother Jenny, written in an indecipherable hand on index cards. Dave didn’t like onions or garlic. Our food was unadorned, bland and unappetizing.

“Make me something light,” I’d say to my mother. To a Russian Jew, of course, this was totally silly.

“What, like feathers on toast?”

Fortunately, I had a friend named Peter Brizzi, who lived around the corner. We used to walk his Basset hound named Caesar around the block and compare notes on growing up. His mother invited me to dinner about once a month and I was indoctrinated into the mysteries of Italian food and homemade sauces, and even a tiny glass of Chianti to go with them. His older brother played the bongos and was a bit of a Beatnik.

Back at home, I came to hate pot roast and meat loaf. The lamb chops and mashed potatoes weren’t so bad. She made tasteless frozen vegetables and Uncle Ben’s rice. Everything was overcooked. On the other hand, Wisconsin processed cheese and grape juice were always in the fridge. Rhoda taught me to enjoy cookies and milk and Howard Johnson’s coconut ice cream, which we shared while watching The Alfred Hitchcock Hour on TV from her bed. Dave and I watched pro wrestling together in the den. I learned to eat with chopsticks at the local Chinese restaurant.

Around my seventh birthday in 1960, Dave drove me to see a piece of land he had bought with a partner. The weeds were taller than I was and I couldn’t imagine a building could be built there. Much of New Jersey’s industrial land is swampy, and early on, engineers from Holland were flown in to teach Jerseyites about water management.

In those days, rather than taking a core sample, there was a cheaper method of determining how deep the solid earth was under the topsoil. You would rent a pile driver and they would hit a pile and see how far it sank. If it went down three feet or ten feet, that meant different softnesses of the earth. Dave’s contractors hit the pile on that site and a 50-foot stick completely disappeared into the earth. They got engineers out there and the core sample showed that the rocky bottom started 90 feet down. Any building would have to rest on piles, a very expensive way to build.

Dave and his partner sold the site at cost. The buyer built an office building with gold-tinted glass, which was fine, but the parking lot, which of course wasn’t on piles, sank about two feet every year. They would add fill and pave over it and the next year, it sank two feet more.

When I was 12, Rhoda found me bored and sulking in a corner and said, “Come with me. We’re going to start you in music school.” No doubt this idea came from her first husband, who played piano to accompany his voice students. We went to a school on Teaneck Road where some defrocked orchestra members taught harmony and sight reading. I bought my first cheap guitar, with nylon strings and horrible action, and learned “The Volga Boatman,” among other classics. After a year, they took me to a real music store and I bought a Gibson Firebird electric guitar. I wore the frets completely flat in about three years. They bought me a Gibson Ranger amp to match, with four 10” speakers and a spring reverb, and its sound was fantastic, like bells and horns. I used to make my own fuzz tone pedals and tortured my parents from our basement with inept renderings of “Satisfaction”, “Purple Haze”, “Sunshine of Your Love”, and other hits of the era. My first band was called Filet of Soul and our first gig was a bar mitzvah. We sucked but we got paid.

That music school was the best thing Rhoda ever did for me.

I spent the entire Fischer-Spassky match in 1972 flat on my back with mononucleosis, watching helplessly from bed. It was the longest I had spent at home in two years and Rhoda brought me up to date about her friends the Dorfman’s and their daughter Debra, who was known as Didi. “Did I tell you that Didi got married and moved to the Mediterranean?” she asked me.

My jaw dropped. “That twerp got a life? That’s amazing! What country?”

“What country what?”

“She got married and moved to the Mediterranean. What country?”

Rhoda looked at me as if I were beyond help. “No, no,” she snorted, “the Mediterranean Towers in Fort Lee. She married an accountant.”

After some peripatetic years, I came back in 1980 with a vision of working in real estate for ten years and then going back to San Francisco to live. It took 28 years to move out, and I didn’t get back to California for 31. Moreover, I do not recommend anyone try to work with their father.

Dave set out to train me while I studied for my salesperson license. He instinctively made me into the good cop while he took the role of bad cop. Our first task was leasing a warehouse in Jersey that was going to be vacant a few months hence. This involved some renovation and some negotiation with brokers. One broker took us to New York’s Garment District to meet a prospective tenant. We toured his sweatshop and then in his office, we learned that he was smack in the center of our main business, which was moving garmentos from the city out to the suburbs. Our typical tenant would shrink the New York operation to a small showroom and put all the sewing and distribution in New Jersey. Typically, the executives lived in New Jersey as well. We learned that he recently had been married and that his business had expanded to the point where he needed more space.

Outside in the street, Dave commented, “I guess the wife has some dough-re-mi.”

The broker was offended, “He worked hard to get where he is.”

Dave’s silence indicated that he wasn’t impressed and that his cynical interpretation would stand.

The next prospect was brought to us by an old-timer broker, who took one look at Dave and refused to introduce his customer unless we signed a listing agreement. The broker told me privately that Dave’s reputation for paying commissions wasn’t good. We signed and learned that they had an oversized women’s clothing business from Canada named Penningtons. They would require an outlet store with oversized fitting rooms and extra-heavy air conditioning, as well as a larger exit door and wider steps to the ground.

We came to the final negotiation at their hotel and the broker sensed we were close to a deal but Dave just wouldn’t say yes. I thought the offer was good enough but Dave became strangely silent. The broker put us in a separate room off the conference room and kept the pressure on Dave to say what he wanted—more rent, more security, what? Dave excused himself and while he was in the bathroom, the broker shook his head. “Do you know what your father is holding out for?”

I also shook my head, “No idea.”

“Your father is inscrutable,” he told me, “like a Chinaman.”

When he came back, the broker went out for a minute. I told Dave, “The broker can’t get you anything if you don’t tell him what you want.”

Dave looked at me, “Tell him you want the parent company to sign as guarantor. Not the U.S. subsidiary alone on the lease.”

“OK.” This was a reasonable request, and one we could work with. We didn’t know how established their U.S. subsidiary was and we wouldn’t want to be left in the lurch if the parent disappeared. We got that provision and signed.

Back at home, I asked Dave if he wanted the parent on the hook for any ah, psychological reason or if he were sincerely afraid that the parent would have disappeared on us. He frowned at me, “Michael, you’re too smart for the real estate business.”

“Hey, I’m losing IQ points as fast as I can.”

“Just play dumb,” he said. “Act natural.”

I sighed, “Isn’t that like my mother calling me a son of a bitch? I made the deal, yes? Why can’t you just say, ‘Good job,’ like a normal father?”

In 1981, I went to work for a real estate brokerage that had a very practical approach. These were real street fighters, and their territory consisted of the worst of New Jersey’s aging industrial buildings, most built in low land about 50 years before, much of it dilapidated, rat-infested, and in dangerous areas. I made a couple of small deals but displayed little talent for sales. I naively told the truth far too often to be effective.

Starting in 1982, Dave and I were partners. I drove him around New Jersey looking for industrial land. I would drive up to his Fort Lee high-rise from my East Village townhouse flat, and we would visit industrial parks or meet brokers together. We found reasonable pieces in Twin Rivers Industrial Park, a part of East Windsor not far from Princeton and the New Jersey Turnpike. Dave seemed to be mostly interested because the sites were near a Jewish temple and he thought this meant a hardworking populace in the immediate area. We bought two pieces of about four acres each, and I developed them, taking the land through the permit process, which in those days was only beginning to be a nightmare, and building about 35,000 square feet on each site as of right with few variances.

Dave was not long on gratitude and never said, Thank you. Instead, he said, “What did you do with yourself today?” or “You understand that, don’t you?” or “I’ll tell you what to do….” I served him because my self-worth was based on being needed, and that was because I had low self-esteem based on comments like this all through childhood. For years, I patronized people in the same way that had been done to me. I’m over that now.

One day I brought Joe, the drummer in my band, up to meet Rhoda. She took one look at him and said, “Aww, he’s sweet. He loves you, Michael.”

The next year, I brought Manolo, a witty Spanish diplomat and translator. Rhoda opened the door and Manolo got her number immediately. He clicked his heels, bowed, and kissed her hand—actually, his finger that was grasping her hand. She shivered with pleasure.

She was far less pleasant with my girlfriends, whom she uniformly detested as unkempt and homely, and even said so to their faces. When in 1985, after two years, she insisted on meeting my fiancée, I told Rhoda how it would go down. “I will pick you up at home and drive you to the Russian Tea Room next to Carnegie Hall. Carol will take the subway up. We’ll have a nice lunch of blintzes. If you make one rude remark, I will instantly drive you back home and you won’t meet her again.” She agreed and the afternoon went peacefully. I got a call from Dave at around 6—Rhoda was in the hospital with a diverticulitis attack that the doctor said may have been caused by nerves. Carol was upset to hear this but I said, “At least she made herself sick, and not us.”

In 1987, Dave and Rhoda sold the Fort Lee place and retired to Miami Beach permanently. I told him that his old Cadillac wouldn’t survive another trip down from New Jersey and he might consider buying a smaller car that would be easier to drive. He decided on an Oldsmobile. We went to the dealer in Hackensack, selected a car, and the salesman said he’d need a couple of days to put in the radio that Dave had selected. He’d need a hundred-dollar deposit to hold the car in the interim.

Dave took a one-dollar bill from his wallet and offered it to the salesman. “Here. Now it’s a legal contract.”

The flummoxed salesman said, “Just a minute,” and ran to get his boss.

The boss came over, took one look at Dave and turned to the salesman. “Just take it,” he said. “One dollar from this man is worth a hundred from an average guy. This man doesn’t waste money.”

I was astonished at his perspicacity. “You know, you’re absolutely right. The pain he’s put me through over even one dollar is amazing.”

I used to visit Dave and Rhoda at their apartment in Bal Harbour, an ostentatious part of Miami Beach that featured an expensive mall across from their building. The whole village was one-third snow birds wintering from Detroit or New York, one-third wintering from Argentina, and one-third year-round residents. Many of the Latins were also Jewish. Periodically someone would speak Spanish to Dave but he would just shrug. I think it was his attaché case, which looked like it was stuffed with Argentina-bought hundred-dollar bills but only packed his underwear and a copy of his Will.

For ethnic relief, I would drive their car to Calle Ocho and 15th Ave. to play chess with the Cubans in a little park. We would take turns buying each other the sugary Cuban coffee in a small cup and pour that around for everyone into tiny Dixie cups, and it wasn’t long before I was flying from the caffeine, the Spanish, and the pressure of clock chess. Instead of “Check, schmuck!” like in the West Village, it was “¡Jaque, coño!” Not so different.

Dave bought Muriel and Murray a condo not far from them in North Miami Beach. Murray got Alzheimer’s, which was sad, because he always had been so sharp. He got out of the apartment and was found wandering in traffic on Collins Avenue. Muriel bought six locks for their front door and locked four of them. After that, he never could figure out how to get the door open because he would lock some of them in the process of unlocking others.

After he died, she became the family comic. She used to joke about being near death. “Michaelie, I don’t even buy frozen food!”

Rhoda was middle-class vain. I assisted her to check-in to a hospital once and her birth date didn’t add up to her claimed age. Everyone just smiled and the nurse and I computed her real age.

When she died in 1992, Dave asked me at the graveside to make a speech. The rabbi came by and asked if we were ready so I took him aside, “I have no idea what to say about my mother.”

“Was she a good mother to you? A loving person?”

“Uh, no, not really?”

“Did she teach you anything?”

I should have mentioned the music school but in the moment, I just shook my head, “Nope.”

“Was she a good cook?”

“No way.”

“There must be something you can say about her.”

“Well, she knew how to choose fashion accessories.”

“That’s good, say that.”

“And she always wanted to be accepted as a citizen in New Jersey, which wasn’t easy for a Jew in 1953.”

“That’s perfect.”

So that’s what I said. People even cried about her accessorizing. I was still mystified.

After Rhoda died, Dave got into the habit of visiting Muriel. On the phone, she would complain to me about her brother-in-law. “Dave is so impossible. He brings me roast chickens and invites himself for dinner, and he laughs at his own jokes. It’s horrible!”

“So why do you let him in?” I asked.

I could hear her shrug, “I need the chickens.”

After Muriel died, her younger brother Al had to take over the role of family comedian. He did have a good sense of humor but despite his willingness, he was no vaudevillian and he knew few jokes. He didn’t know the material; he had little in the way of shtick. He worked as a salesman in a classy luggage store next to Bergdorf’s on Fifth Avenue, and Indian princesses would come and buy twenty Louis Vuitton suitcases at a shot, in which to put the furs they had purchased for their friends back home. I get a large picture of them wearing furs in India’s 110° heat.

In the army, he had crawled across Africa and Sicily, and he had PTSD bad. One day he met a guy from his division standing on the corner of Fifth Avenue and 58th Street. “Fred! Haven’t seen you in a dog’s age! What are you doin’ here?”

“Takin’ a shit,” Fred answered. He had a colostomy bag from his injuries.

Al was an extremely good-natured guy. After surviving the war, everything was delightful and borrowed time to him. He married a woman who liked to drink a bit too much. They had met at a hotel bar on Central Park South while watching Oscar Peterson play jazz piano with his band. They had one son, and they divorced when the son was a teenager. My father put the kid through chiropractor school and he settled in Seattle. I’m not sure if Dave ever knew he was gay.

Al got a job in a luggage store in a Miami mall, mostly training the youngsters in the shop. He couldn’t make too much money or he’d lose his Social Security benefits but he took a lot of the stock and gave everyone leather presents. There was another luggage store in the mall, a competitor, and one day near the end of a month, Al noticed that they had put all their goods on tables in front of the shop with discount tags. Al deduced that it was a rent sale. He immediately put all their stuff on tables in front of their shop. The other guys closed a week later.

My father had the attorney from hell, who got his hooks into him after Dave and Rhoda moved to Florida. Even Muriel called him “that prick.” His Will was terribly written, a real joke of lost syntax and vague antecedents. One day while visiting Dave in Miami, I found a yellow 9 x 15” mailer on the table, opened it, and found in it a Will that completely cut me out. After dinner, I told him I had found the new Will. “Look, it’s your money. You can do whatever you want with it, including leaving it to the United Jewish Fund or whatever. All I ask is that you tell me in advance. I think that’s fair, don’t you?”

He didn’t respond but I could tell that I had reached him.

I realized that he was very litigious and never told him that I knew my birth mother for fear he would sue her or disown me. One night, he took out a small photo that I recognized. “Have you ever seen this woman before?”

I played dumb, as he once had instructed me. “Who is she?”

“She was your mother.”

“You mean my birth-mother in 1953?”

“Yes.”

“Huh. I didn’t know. Anyway, Rhoda was my mother. I don’t know this lady,” I lied. “Is she still alive?”

“I don’t know.”

“That makes two of us.”

Dave died peacefully in bed in 1996. I wasn’t there—only his Jamaican nurse witnessed his end. I chose a pompous coffin that he would have liked and at the funeral, I read my eulogy, “The lesson for us contained in David Simon’s life is always to speak directly so we won’t be misunderstood. Tell those close to you that you love them, lest they never figure it out. Tell them with words, with good feelings, and with humor and loving-kindness, so they never have to guess at these feelings by your actions.”

I thought it was kind; the relatives thought it was terribly disrespectful.

We put the coffin in the ground and saw the footstone ready to be placed after the burial. It read, “David Simon, 1904-1996, a fierce sparrow falls.” I explained to the crowd about his Pierce-Arrow but the relatives all thought I was crazy.

Uncle Al and I were walking away from the grave and he was uncharacteristically irritated by my eulogy. “Someday, you’ll put me in a hole inna ground, trow dirt in my face, and read a speech like dat.”

“Oh?” I replied. “What are you doing Thursday?”