I watched the entire Fischer-Spassky chess match in 1972. Professional play is completely different from amateur games. For one thing, many amateurs play “blitz” or chess with a chess clock. A chess clock has two clocks, which add up the cumulative time each player has used. You move and push your button, which stops your clock and starts your opponent’s. Skilled players play through known openings very quickly, reaching well-known positions called “tabia” before slowing down and beginning to think. Many have memorized opening books, which recommend the best moves up to a point and deal with unusual or trick openings.

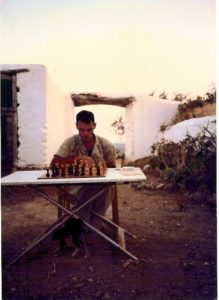

While attending the University of California Santa Cruz in 1973, I would ride my motorcycle to a bar called The Catalyst to watch a weird guy with a huge beard and long Mandarin nails entertain the troops. And while living with my first serious girlfriend in San Francisco the following year, I frequented the two or three coffeehouses where chess was permitted and played. It wasn’t such a good deal for the establishments—the players would play avidly but sit all day nursing one cup of coffee and even asked for free refills.

Although nobody should have to lose a chess game, I tried to immunize myself against the humiliation by telling myself that I was learning with each loss. It didn’t quite work but anyway, I became part of the chess scene in San Francisco, which being compact, afforded me the chance to meet some of the best players in town, as well as some of the worst. There was a coffeehouse on 24th in Noe Valley called the Meat Market because it had formerly been one and still had rails and hooks for animal carcasses. The name was misleading—you were unlikely to find sex there. The back of the shop was the chess area with a main table in the center for the best players and various deuces ranged around it for patzers like me.

Chess seemed to me to be utterly worthless socially and politically, completely outside the monopoly of our time by school, jobs, police, and the army. By 1978, I had been in schools for 20 of my 25 years on the planet. All that education had given me a garden-variety nervous breakdown so rather than do intellectual work, I found daytime employment as a mechanic at Volvo Centrum on 16th Street, fixing and restoring those indestructible round tops of early sixties vintage and the dependable square station wagons of the seventies. By night and on weekends, I played chess.

A fellow named Bob Atlas frequented the Meat Market. He had won the U.S. Open the year before and he told me a useful thing. If you just make yourself sit there and stare at the position in front of you, sooner or later, ideas will occur to you.

There was an old Jewish guy named Sinkevitch at the Mechanics’ Institute Chess Room. A diminutive white-haired fellow with dark sunglasses and a visor, he had been checkers champion of Shanghai in the 1930s. He never said, “Take the queen;” he said, “Kill the lady.” Bishops were “rabbis.” And of course, he used to bandy that old saw, “Take the knight off and mate in the corner.” He also had fun calling people over and asking confidentially, “Do you eat dead chicken?”

I had been obsessed with chess for the last year or so and had advanced to the point where I could play blindfolded. I would turn my back to the board and say for example, “Pawn e4.” My opponent would make my move and then report his answer to me, “Pawn c5.” And so the game would progress. I know this sounds remarkably difficult but these days, professional players have blindfold tournaments, and whereas in the past it was considered a trick that a master would perform, it has become an accepted chess variant. As one learns the language of chess, remembering a board position is equivalent to restating a conversation you had with your friend.

And worse yet, skilled chess players can get into the habit of characterizing people by the openings they favored. “He had a short haircut, ya know, and liked the Dutch. Didn’t carry a backpack, just an empty box of Dutch Masters cigars with his stuff in it…”

My favorite denizen of the Meat Market in those years was an ex-con named Luke Ladow. A tall man with one-eighth Japanese blood, he resembled the young Toshiro Mifune, a contemporary samurai. He was affianced and then married to a beautiful mail carrier, who bore him two sons. He drove a yellow Toyota Corolla that looked like it had been through a war, with its lights hanging out like alien eye stalks, and a milk carton for a passenger seat. No panel on that car didn’t have dents, scratches, or major damage.

Of perpetual good cheer, Luke had his chess patter down. He would move a rook to your second rank and bellow something like, “Pardon me while I rape your wife!” Having faced heaven knows what in jail yard scraps, he never got nervous but would sit calmly as the seconds ticked off his clock, snorting intermittently and finally moving with great confidence. I adored him, as did many of the other chess nerds.

While San Francisco’s chess scene was limited in population, New York’s was sprawling, and I tasted a bit on a visit to my home turf. I liked to visit the chess parlors in the West Village near NYU. At the corner of Sullivan and Third Streets was one belonging to a Romanian philosophy professor named Ionel Ronn. Sue Cowan introduced us. It was a nice enough place just up and around the corner from Café Reggio and an easy sprint from the chess tables in Washington Square Park in case it started raining. The other parlor belonged to a boisterous Ukrainian grandmaster named Rossolimo, or rather to his widow.

The famed Washington Square chess tables were also lots of fun. People often bet $1 or so on the games and a certain number survived on their winnings. Sometimes, a famous player would pass by, like Roman Dzindzichashvili or “Jinji”, as he was called. I played him 1-minute to 5 on the clock just to be able to say I had done so. I had zero chance, of course. It was like playing a ping-pong pro. Jinji had complete control of the game from the third or fourth move.

I met Steve Brandwein at the Game Room under the Beacon Theater. We would play 2-5-minute lessons for $2 a game. Steve was an amazing character. You would walk up and say, “Hi Steve, how ya doing?” and he would reply, “Og is happy. Og has eaten,” or words to that effect. But he had an interesting story, which I heard some years later from Paul Whitehead.

An Assistant Professor in History at Columbia, Steve was also a senior master by the time of the Fischer-Spassky match. The host Shelby Lyman brought him on his TV coverage of the event and everything went smoothly for a while. After ponderous thought, Fischer played some move or other, rook to king six, which rook could be taken by any number of pieces, each choice having a different result. Lyman turned to Steve and said, “What do you think of this position, Mr. Brandwein.”

Something snapped in Steve’s head and he started ranting, “That Nixon is going to end our democracy. The war in Vietnam is…”

The screen went black while the techs switched to commercial. Shelby Lyman lunged for Steve’s throat. Columbia kicked him out and he never taught again. He moved to San Francisco for a while to recover.

He lived in a house where Bobby Fischer came to stay and they played some 2-minute games. Now this is remarkable because Fischer had and still has the world record for blitz. He took one minute, played a master-level player with five minutes, and they fought over a French Defense. Fischer played an astonishing 99 moves in less than one minute and won the game.

Notwithstanding, Steve won a full 20% of the 2-minute games he played with Bobby. Wow, right?

I whiled away the hours playing, time passed, and somehow, I improved. I came to realize that in chess it is often the person who makes the next to last mistake who wins. I found a meditation in the astonishing boredom of sitting and waiting for your opponent to make a mistake.

I met Sue Cowan in Vesuvio’s, the historic bar next to City Lights Bookshop in San Francisco. I could easily see that she was hustling. She would play a few games with guys, let their egos get into gear, and then suggest playing for a modest bet. Suddenly she had complete command of the board. The guys would lose a few, pay up, and depart in disgust. I sat down at her table and told her, “Look, I know what you’re doing. I won’t play for money but I humbly request a game.”

“Sure,” she answered, setting up the pieces. She won and we got to talking. The only child of the only Jewish family in an Ohio town where they had the only shoe factory, Sue used to pass a used bookshop every day on the way back from school. She became friends with the owner, who one day warned her that she would close the shop and go out of business soon. The store barely made the rent and was more of a lifestyle than a business. Sue offered to take it over and soon bought it for one dollar. Every afternoon, she would sit from the end of the school day until dinner and run the shop. Again, it barely made rent but Sue read all its books. When they closed it so they could tear down the building, she just walked away clean.

I invited her home and she stayed for three months or so. Sue was a petit mal epileptic who could have minor fits in between chess moves without anyone else knowing. She had remarkable command of her brain and body, and could orgasm without touching herself. She and I used to play blindfold chess while standing on movie lines waiting to get in. We would get into heated fights, “Your bishop was on b7!” “It was not!” One night, the couple behind us asked what we were doing. I guess we were a bit odd.

We invited a master named Paul Whitehead over and played while taking LSD. If you’ve ever seen the youtube site called “hikea”, where people take acid and then try to assemble Ikea furniture, you can imagine what our games were like. Lots of giggling was involved.

Even at 16, Paul was connected to the highest echelons of chess and gaming in San Francisco. He invited us to a barbecue at the Palo Alto home of a player named Jones. Jones’ wife was Japanese and she managed to cook for the fifty guests with apparent ease. There were two rooms devoted to games—one for two-minute chess and another for every other kind of chess and other games like Scrabble.

A grandmaster named Walter Browne was there. Browne was writing a book about queen vs. rook endgames and would take either side of the following bet. White had the queen and 10 minutes while Black had the rook and 5 minutes. White had to either checkmate or win the rook within 50 moves or he lost. Watching Browne play was intense. He would hunch tensely over the board and it seemed as if a feather falling on him would shatter him like glass.

Everything was going fine but one day I realized that Sue and I were the wrong crazy for each other. I sat her down and asked her, “If you could be anywhere in the world right now, where would you wanna be?”

Sue thought a minute, “Amsterdam. Yeah, I have great friends in Amsterdam.”

“If I bought you a one-way plane ticket, would you get on the plane?”

She blinked and considered a split second, which was long for her. “OK.”

I did and she did.